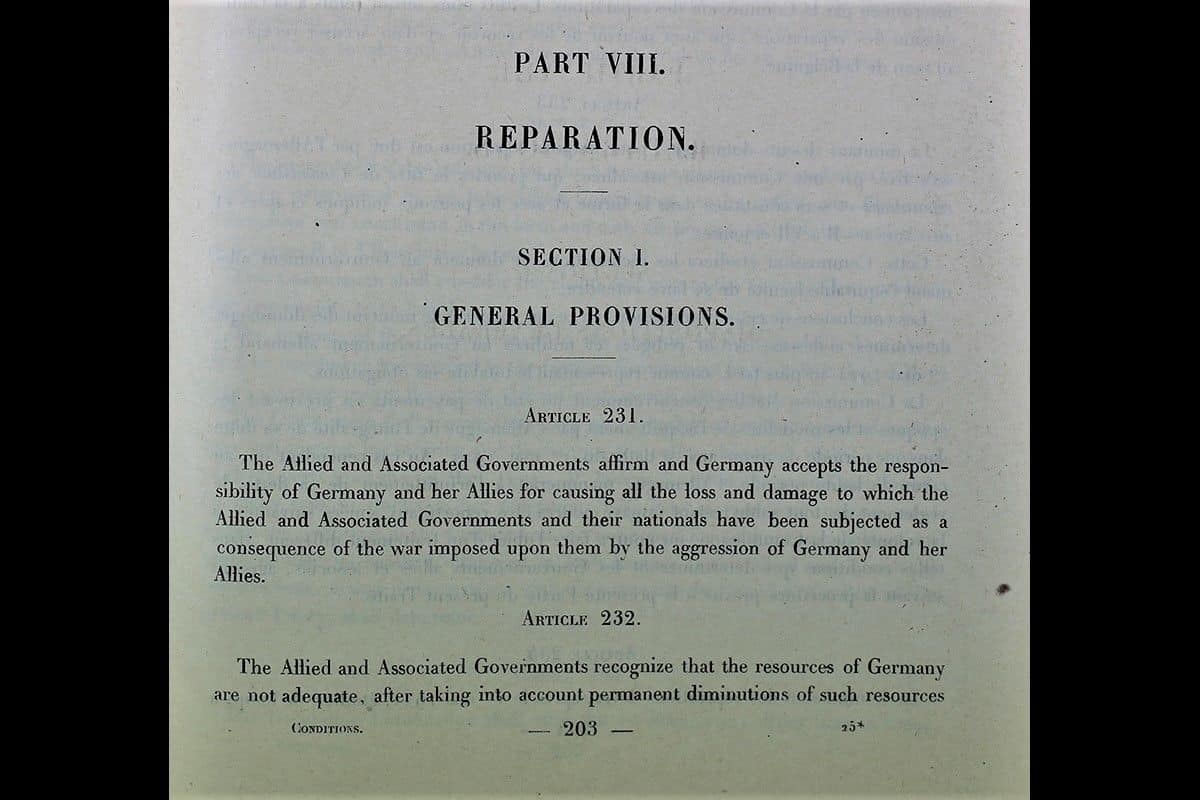

The value of paper money disappeared so quickly that some companies paid employees in the morning so they could rush off and spend their wages at lunchtime. The rapid devaluation of paper money caused ludicrous scenes. By November, the Treasury reported there were 400,338,236,350,700,000,000 (400.3 billion trillion) Reichsmarks in circulation across Germany. On one day alone, October 25th 1923, the Weimar government released banknotes with a face value of 120,000,000,000,000 (120,000 trillion) Reichsmarks – while announcing plans to triple its daily output. By 1923, the largest-priced stamp cost five billion Reichsmarks – but even this was not enough to post an ordinary letter. The face value of postage stamps also skyrocketed.

The denomination of banknotes increased, the largest note with a face value of 100,000,000,000,000 (100 trillion) Reichsmarks. This cycle of inflation and currency releases spiralled through 1923. The Weimar government was not strong enough to fix wages or prices, so its only response was to issue more paper money. In 1923, the market price increased to 500 (January) then 30 million (September) and four billion Reichsmarks (October). One dozen eggs cost a half- Reichsmark in 1918 and three Reichsmarks in 1921. In 1923 the market price for bread spiralled, reaching 700 Reichsmarks (January), 1200 (May), 100,000 (July), two million (September), 670 million (October) and then 80 billion Reichsmarks (November). Prices and denominations soar German children are photographed launching a kite made of worthless banknotesĪs more banknotes went into circulation, the buying power of each Reichsmark decreased, prompting sellers to raise prices. In 1918, a loaf of bread cost one-quarter of a Reichsmark by 1922 this had increased to three Reichsmarks. At the height of the crisis, Germany’s state governments, major cities, large companies, even some pubs were all issuing their own paper money.

Ironically, the production of paper money became one of Germany’s few profitable industries. Paper money was continually pumped into the German economy, leading to devaluation and hyperinflation.īy mid-1923, the nation’s central banks were using more than 30 paper factories, almost 1,800 printing presses and 133 companies to print banknotes. But as the Ruhrkampf continued into the summer and autumn of 1923, no alternative way could be found to address the crisis. Government economists understood the dangers of flooding the economy with paper money, so the policy was intended to be temporary. It did so by increasing print runs of banknotes, a policy the government had been using intermittently since 1921. Despite its parlous economic condition, the Weimar government decided to support this strike by continuing to pay striking workers.

In early 1923, German workers embarked on a prolonged general strike as a protest against the occupation of the Ruhr by French troops.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)